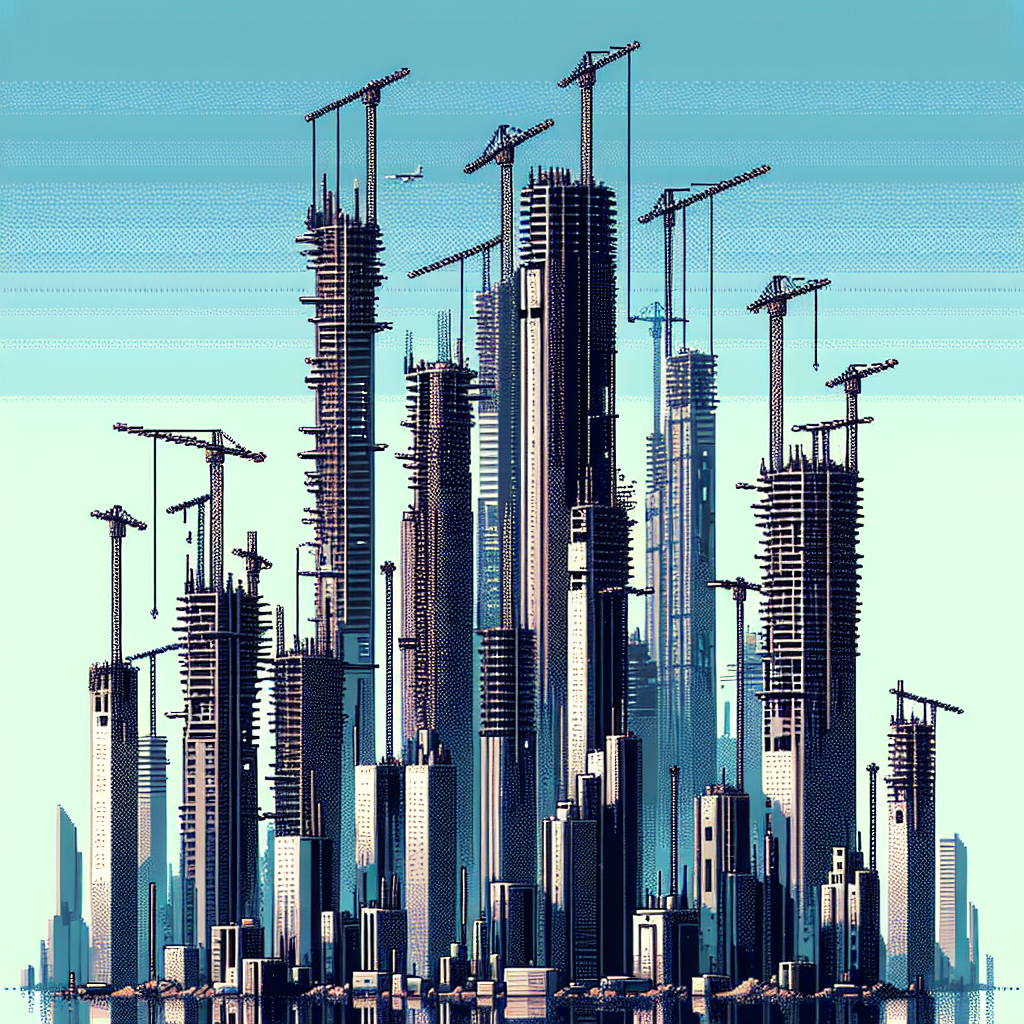

S.F. Developers Face Tough Reality as Optimism Meets Market Slowdown

In San Francisco's stalled real estate sector, confidence has long been a developer’s currency. But as deals drag and capital dries up, the line between strategic patience and misplaced optimism

In San Francisco’s stalled real estate sector, confidence has long been a developer’s currency. But as deals drag and capital dries up, the line between strategic patience and misplaced optimism is getting harder to define.

At the center of this tension are projects like One Oak, a proposed 40-story residential tower at the intersection of Market Street and Van Ness Avenue. The development, first proposed in 2015, gained approval in 2017. Developers broke ground in 2021 but quietly stopped work soon after. The site remains a fenced-off pit, with no clear timeline for construction to resume.

The One Oak project is not an isolated case. Just a few blocks away, Build Inc.’s 26-story tower at 469 Stevenson Street was abruptly halted last year. The City had approved the project in 2021 despite controversy, but market conditions and financing constraints forced the pause. Another planned high-rise nearby, a 55-story condo building at 10 South Van Ness Avenue, also faces delays. Its construction was initially projected to finish in 2025, but work has slowed.

These slowdowns reflect a broader uncertainty hanging over San Francisco’s real estate market. While developers publicly express faith in the city’s long-term demand, private conversations suggest growing hesitation. Land prices remain high. Interest rates climbed. Remote work hollowed out core demand for housing near traditional job centers.

The result is a growing inventory of permitted but unbuilt towers. According to the Planning Department, San Francisco has approved roughly 9,000 housing units that have not yet moved into construction. Some of those approvals date back five or more years. Planners say delays are tied to rising construction costs, weakening investor interest, and questions about whether enough buyers or renters will materialize to fill new units.

In one telling example, the HUB District, marketed in the last decade as the city’s next major development zone, has seen multiple delays. The district was expected to deliver thousands of new homes clustered near key transit hubs. But heavy reliance on high-rise construction and luxury units has made the area vulnerable to economic shifts.

Developers say they remain committed and still believe in San Francisco’s long-term recovery. Yet few have updated their timelines publicly, and many are avoiding new groundbreakings entirely. Financing remains scarce for large-scale projects not already underway. Construction costs have held steady at around $500 to $600 per square foot for high-rise buildings, a level many lenders no longer see as viable given current sale and rent prices.

Some projects are looking for creative solutions. Build Inc., developer of the Stevenson Street tower, has hinted at redesigning the project with fewer stories or different financing partners. Others are waiting for interest rates to drop or hoping for new city incentives. The Board of Supervisors last year passed legislation to speed up permitting, but developers say red tape remains a major burden.

For residents, the result is an increasingly visible disconnect between policy goals and lived experience. City leaders say they want to solve the housing crisis. Yet entire blocks sit dormant behind fences, approved towers frozen in limbo. The question is no longer just about timelines but about underlying confidence in the city’s future.

As more developers pause and revise plans, San Francisco’s housing pipeline risks contracting just when policymakers are trying to expand it. The city needs more than optimism to reverse the trend. It needs projects that pencil out in today’s harder math.